Today was parent-teacher conference day with #1’s homeroom teacher. I’ve been to 15 of these now for #1 (and another 9 for #2). And although I have tried always to be involved in his school—I frequently help out or have chaperoned field trips or talked to the class about what I do—I still make a point of of attending parent-teacher conferences. On the one hand, parent-teacher conferences help me understand the school’s broader curricular goals and how he is progressing toward those goals: what he is learning; how he is learning; what challenges he might be confronting. On the other hand, parent-teacher conferences give me a glimpse of a #1 that I don’t see: what he’s like around his peers and in other social settings; how he behaves in public. There’s another reason I attend parent-teacher conferences, a reason that seems to get lost in the shuffle (or, for so many parents and teachers trying to carve out a few minutes from an otherwise frenetic dash through the day): I go to parent-teacher conferences because it means a lot #1.

Yesterday I mentioned to #1 that I was looking forward the parent-teacher conference. My comment was a sort of warning—our conference was before school, so we would have to be efficient in the morning and leave earlier than normal. He looked up and asked hopefully: “Is mom going?” He seemed to deflate when I said, “No. She has to go to work.”

—“Why doesn’t she go to my teacher conferences?”

—“She trusts you and me. You’re a good kid and good student. I don’t think she feels a need to check in on you.”

—“But she never goes to mine. I wish she would.”

His lament reminded me how important it is to kids that parents show a real interest in their education, in what they do every day, i.e., in what we make them do every day. Parent-teacher conferences are about more than just establishing lines of communication or building working relationships between parents and teachers. Parent-teacher conferences also bolster relationships between parents and children.

Parent-teacher conferences are stressful a lot of work for everybody. Parents have to adjust schedules, often have to find childcare for a younger sibling, and have to make special trips to school, where they hope won’t be kept waiting while other conferences run long. And then there’s the worry that they’ll find out darling Tobias or little Beatrix is a terror or failing or …. Teachers have to prepare for conferences, adding to their otherwise already full day’s work, and then have to take time that they could be prepping for class, helping students who need a little extra, or grading. And then there’s the concern that some parent is going to erupt because their perfect child couldn’t possibly be failing, or be disruptive, or be an unrepentant pain in the ass. For different reasons, parents and teachers can be anxious about these conferences.

Parents who want to improve the experience can find useful advice. Grete DeAngelo offers some nice tips for parents (reposted at Huff Post (because isn’t everything these days reposted at Huff Post?) and Topical Teaching). Lisa Heffernan at the WaPo compiled her own list for parents: Learn from my mistakes. Beth Van Amburgh offers some general tips that are handy for both teachers and parents.

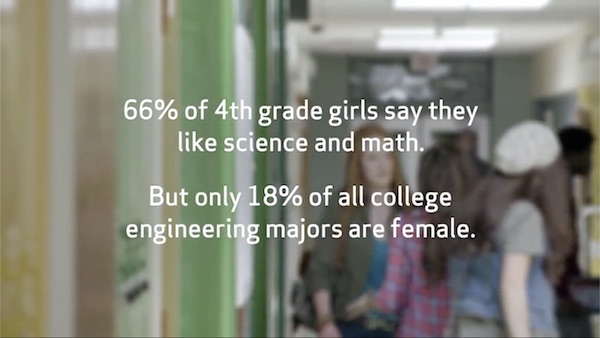

With all this focus on parents and teachers, on classroom performance and behavior, it is easy to lose sight of the people standing at the center of this educational, social, and by middle school hormonal maelstrom. It is easy to forget that for kids, school is incredibly important and daunting and at times disorienting. They are not experts at negotiating the dynamic and shifting relationships. Nor are they as jaded as we often think. They are kids who still look to their parents for guidance, affirmation, and approval. They want to see that we care.

This morning #1 and I walked into school. As he led me to his class, he pointed out various things hanging in the halls—art work, projects, assignments—and shared comments about some of the other classrooms and teacher. Then he returned to the cafeteria while we met with his teacher. When I left, #1 walked me to my car and peppered me with questions: How did it go? Did I like his teacher? Did I see the class turtle? Did I see the fish? Did we talk about their science project? Did the teacher show me the poster they made? Did …? Did …? Did …?

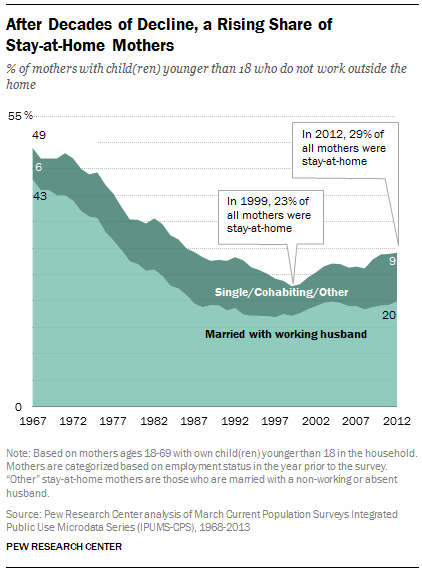

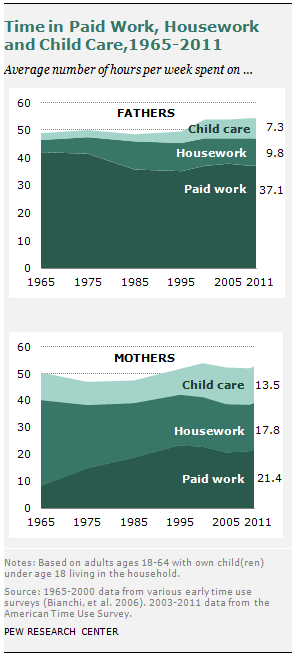

The next chance you (especially you dads, since mothers typically bear the burden of school-related events) get, go to a parent-teacher conference. It‘s an easy way to show your child that you care.

You must be logged in to post a comment.