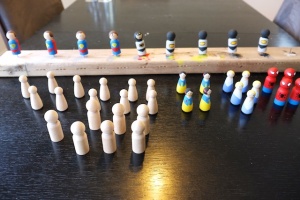

During our recent afternoon of making fairies #2 reminded me of the weekend we spent making peg princesses and superheroes. We were trying to come up with something small to give her classmates at the holiday. I recalled seeing wooden peg dolls at the local crafts store. So I did a quick search and found lots of moms (unsurprisingly, I found no dads) making peg dolls (this was our model; she modeled her dolls on this page; there are beautiful examples if overly ornate for our purposes; and of course you can buy them on Etsy). These are all very nice but didn’t seem quite what I wanted. My goal was something #2 could do so we could work together on them. I was less interested in distributing gifts to her classmates than I was in spending a couple days working on a project together. So our army of peg princesses and superheroes was born.

Setup and materials—

We bought a couple bags of wooden peg dolls from here. I drove finishing nails into a 2×4 and cut off the heads so that we could hold the dolls as we painted them.

I then drilled a little hole in the bottom of each doll.

Paints and brushes came from the local arts and crafts store.

Painting—

Then we had to think about how best to paint them. With a little masking tape and some forethought, you don’t have to worry about so much about the fine details the 6-year-old fingers can’t quite master. We made the princesses and superheroes in batches, sort of a peg-doll production line. I did the finish detail—e.g., faces and superhero emblems—but #2 was able to do everything else.

By the end of the first day we were about half done.

We returned the next day and finished them off. When they were all painted, I sprayed them with a clear coat to give them a nice sheen and to protect them from chips, stains, and water.

The only drawback, if there was one: when #2 told her classmates that she had made the dolls—she was quite proud of her work—they believed her. Some of the parents, however, were convinced we had purchased them—I had to reassure those parents that #2 was not lying, we had really made them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.